The United States is riveted by the ongoing trial of Derek Chauvin for the death of George Floyd, who died in visible mental distress. The debate continues to rage on the proper scope of law-enforcement’s rule in addressing mental-health and substance-abuse issues after the high-profile death of Daniel Prude. With this fraught social backdrop, the Supreme Court is set this Term quietly to decide what role the Fourth Amendment should play, if any, in the execution of the police’s “community caretaking functions” in Caniglia v. Strom.

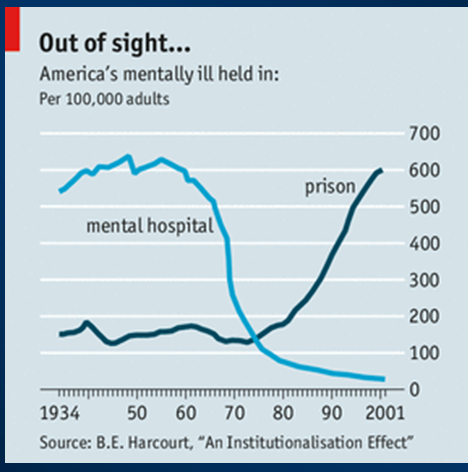

It is no secret that in contemporary American society, the criminal adjudicatory and penal systems have largely replaced the mental-health apparatus available before the 1980s. As Bernard Harcourt illustrates in his Illusion of Free Markets, hospital beds available for the mentally ill have been almost entirely replaced by cells in jails in prisons since the late 1970s.

As a result of this social focus toward incarceration, local law-enforcement officers have become the principal first responders in dealing with mental illness and related issues. These beat cops, many of whom mean well, are not often fully trained on how to deal with the issues raised by mental health and similar problems of “community caretaking”. But more importantly for us, does the Fourth Amendment regulate police conduct in exercising this “community caretaking” function? If so, by how much?

The story begins in sharply divided decision that does not meaningfully implicate the modern role of the police as first responders to mental health crises. In Cady v. Dombrowski, 413 U.S. 433 (1973), Chester Dombrowski, a Chicago police officer, was arrested for drunk driving following a single-car collision in West Bend, Wisconsin. Believing that Chicago police officers were required to carry their service revolvers at all times, the Wisconsin police searched Mr. Dombrowski’s person but could not find the gun. So, they searched his car, without a warrant, and without probable cause, and discovered a bloodied car mat. Confronting Mr. Dombrowski with this information, he provided a statement leading the Wisconsin officers to a body, and, eventually, to his conviction for murder.

The Supreme Court upheld the warrantless search, based on a “concern for the safety of the general public who might be endangered if an intruder removed a revolver from the trunk of the vehicle.” As the Court would go on to write, “the type of caretaking “search” conducted here of a vehicle that was neither in the custody nor on the premises of its owner, and that had been placed where it was by virtue of lawful police action, was not unreasonable solely because a warrant had not been obtained.” In short, the police can conduct reasonable searches out of concern for the general public. But that search, in Cady, is closely cabined to the fact that the gun was located in a car that “was vulnerable to intrusion by vandals,” and the decision was careful to rest its premise on the Court’s “previous recognition of the distinction between motor vehicles and dwelling places.”

Caniglia tests the limits of Cady by presenting the question “[w]hether the ‘community caretaking’ exception to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement extends to the home.” And it also brings into sharp relief the question of what role, if any, the police should be playing in monitoring the mental health of the citizens they are sworn to protect.

On August 20, 2015, Edward Caniglia and his wife, Kim, got into a disagreement in their Rhode Island home. In what counsel describes as a “dramatic gesture,” Edward put an unloaded firearm on their table and told his wife, “why don’t you just shoot me and get me out of my misery?” Eventually, their fight ended and Kim spent the night at a hotel. The following day, when Edward did not answer the phone, she called the police to make a “well call” on her husband. The police escorted her home and found Edward there, acting normally. Nonetheless, the police had Edward involuntarily evaluated by a psychiatrist.

While being evaluated, the police entered the home, with neither a warrant and probable cause nor consent, and seized Edwards handguns. A suit under section 1983 of title 42 of the U.S. Code followed, and the First Circuit ultimately determined that the Cady exception extended to the home. The Supreme Court granted certiorari.

The First Circuit was quite clearly wrong: Cady rested entirely upon the fact that the car was a nuisance and was “vulnerable to intrusion by vandals” who could get ahold of a gun. (And, as the reader might well imagine, I do not even think the Supreme Court had Cady right. The police should not have been able to search Mr. Dombrowski’s 1967 Thunderbird without a warrant, either.) The home, on the other hand, has been found repeatedly subject to the highest level of Fourth Amendment protection available; no Fourth Amendment exception could possibly extend so far as to permit the search contemplated in Caniglia. The Supreme Court is very likely to reverse this decision, if not unanimously, then nearly so.

The Fourth Amendment issue seems so clear as to be nearly uninteresting. But the larger social issue at stake is compelling. As a country, we have apparently decided to place tremendous faith in law enforcement, not just to make individualized determinations about criminal wrongdoing while on the beat, but also with momentous decisions about whether civilians are so mentally unwell or out of control as to warrant a spit hoods, chokeholds, or home searches. The line has historically be drawn at the home, and clearly the Supreme Court has a responsibility to uphold that line in Caniglia. But we also, as a community, have to decide if we really want the police, in the form they currently operate, to do the “caretaking.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.